×

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE WORKSHOP KIT

Enter your email below and we will keep you updated as more information is released about the kit.

I had a fabulous question this week: where do we fit ‘pros' and ‘cons' in our storyline?

That is a ‘ripper' of a question.

My answer is this: lists of pros and cons don't belong in your communication, they help you think through that message.

Let me explain.

If we provide lists of pros and cons for an idea, we are providing information rather than insight. This matters, because in taking this approach we

If, instead, we do the thinking for our audience, we will deliver insights that emerge from our own analysis of the pros and cons list.

Although more intellectually challenging, this is better for us and our audience. We know more about the area than they do and we don't miss the opportunity to share our value add.

If your audience is explicitly asking for pros and cons lists, pop them in the appendix. Focus your main communication around your interpretation of that list.

Hopefully next time they won't ask for the list, but rather for your insights.

I hope that helps.

Kind regards,

Davina

I love what I do.

I help senior leaders and their teams prepare high-quality papers and presentations in a fraction of the time.

This involves 'nailing' the message that will quickly engage decision makers in the required outcome.

I leverage 25+ years' experience including

My approach helps anyone who needs to engage senior leaders and Boards.

Recent clients include 7Eleven, KPMG, Mercer, Meta, Woolworths.

Learn more at www.clarityfirstprogram.com

(*) Numbers are based on 2023 client benchmarking results.

Have you ever wondered whether a storyline is the right tool to use when you are not providing a recommendation?

Perhaps you have been asked to undertake some analysis or are concerned that your audience may not want you to be too assertive or direct?

If so, you may enjoy some insights from this week's coaching discussions which conveniently follow on from last week's focus on communicating details.

When delivering analytical findings, particularly to a sensitive audience, summarise your findings rather than synthesising or recounting your analytical process.

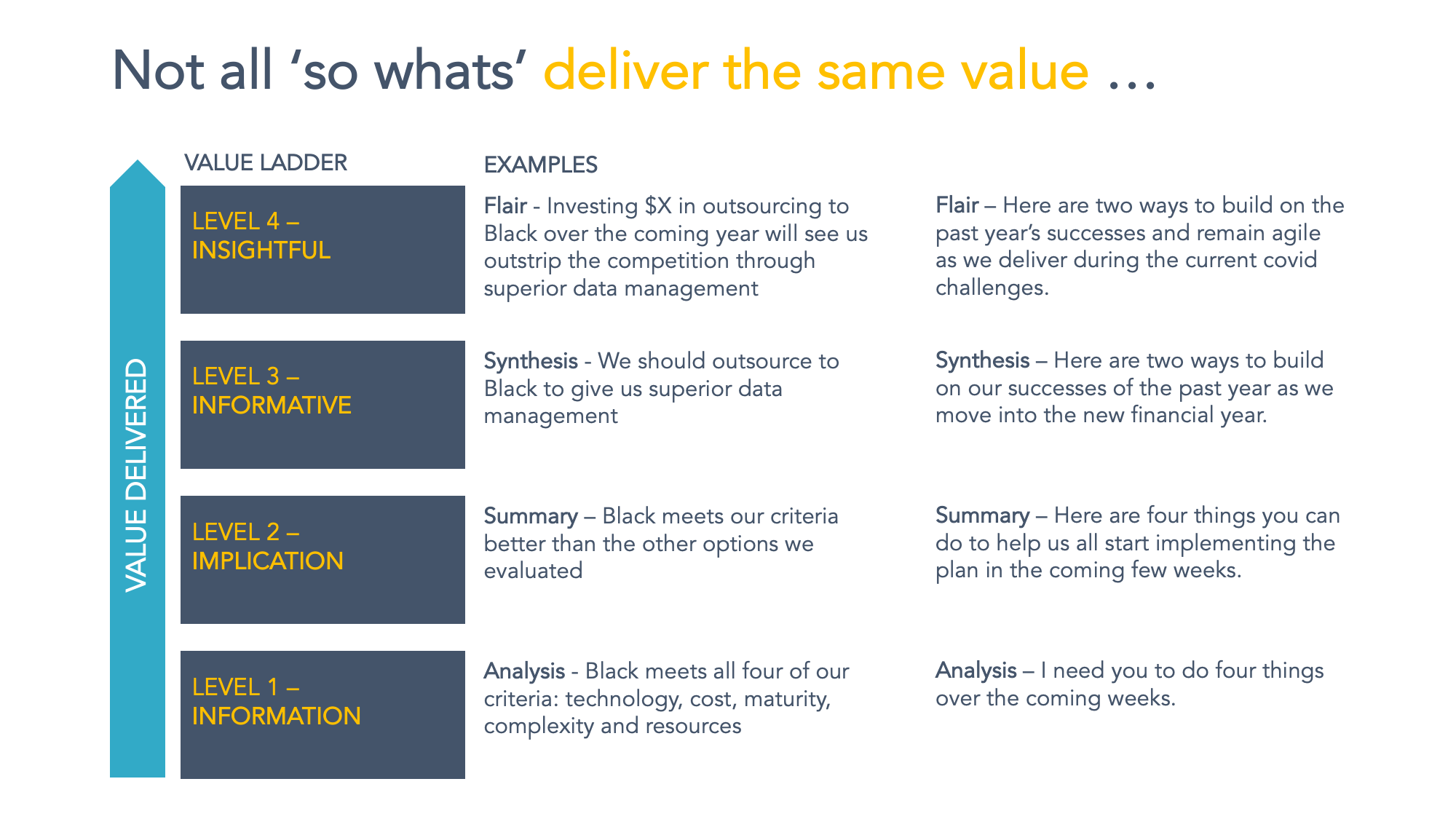

Provide a summary answer rather than a true synthesis. The examples below illustrate how to offer a summary rather than a synthesis:

Avoid describing what you did to deliver your findings, but rather focus on what you found.

This played out perfectly this week when a data analyst in a pricing team for an energy company needed to backtest the pricing model. His goal was to assess whether the model was accurately reflecting the market by checking actual versus predicted market pricing over the past quarter.

The temptation was to explain the steps he took to confirm that the model was accurate rather than explaining that it has proven to be accurate this past quarter because it ‘ticked all the boxes'.

Listing all the steps he took required the audience to work through his analytical process rather than focus on the outcome.

This is a common challenge I see at play among analysts, which could also play out if you were trying to navigate cultural sensitivities about being too forward.

Allow your audience to make the decision if you are concerned about cultural sensitivities around assertiveness.

When I was based in Asia, particularly in Hong Kong helping consultants communicate with mainland Chinese clients, we had to be very careful about how we couched our messaging.

Our advice was not going to be welcome if we were too assertive, and we needed to respect a specific cultural need for leaders to be seen to make their own decisions.

The role of consultants in these contexts is different than in more direct, Western environments so we tailored our approach accordingly.

The example on the left of our value ladder is more useful in this context, with level one being pretty clear that ‘Black' is the way to go without going as far as saying that. Some interpretation is still required by the decision maker, which allows them room to ‘make the decision'.

This approach can be used more broadly when making a recommendation without being seen to recommend.

I hope that helps. More next week!

Kind regards,

Davina

PS – please note that in the example to the right you will see we jump from ‘four things to do' to ‘two ways to help'. This is because in the actual example we grouped the four into two parts as we elevated up the storyline hierarchy.

Complexity is at the heart of the challenge when communicating at work.

In this workshop I address five of the common traps that make it difficult for us to engage others in complex ideas and offer ideas on how to solve them.

Click the play button below to learn more and here to download the handout and here for more program information and here for information for your manager.

CHOOSE THE LEARNING PATHWAY THAT SUITS YOU BEST …

1 – Board Paper Bootcamp – For those who want me to guide their learning journey. Complete online modules in own time and join 4 x highly interactive 90-minute workshops to practice and master the approach. Typically run each quarter, learn more here >>

2 – Clarity Hub – A self-directed option with access to a rich collection of resources, tools and templates as well as regular live working sessions and the ever-useful Pattern Picker. Join anytime here >>

3 – My Books – With Elevate and Engage, my books will help you lift the quality of your board papers and communication without the endless reworks. I share my practical approach which you can implement straight away, learn more here >>

This was the best course I have done. I was always confident in my reasoning but not as confident with presenting it, particularly to audiences that were not on my wavelength.

Davina has shown me how to organise my high level messages which gets me a better response from my audiences.

In fact, when I used the approach to present to the sales team last week half of them came up to me individually afterwards to compliment me on my presentation. That has never happened before!

Clarity First was incredibly useful for me as it has provided a framework through which I am able to structure my initial thoughts quickly and easily.

I have always been OK at delivering communications, but the tools Davina has taught me will not only make the communications clearer and more concise but the time taken to get to the end point has reduced greatly.

I recommend the course to anyone who wants to make existing skills even better or for those that want to create the foundations for great communication.

Keywords: Art and Science of communicating complex ideas, workshop, free

It might shock you to know that our brains are quirky and more like Homer Simpson's than we realise.

In Thinking Fast and Thinking Slow, Daniel Kahneman describes how we lie to ourselves just like Homer does.

He suggests that we make up stories in our minds and then against all evidence, defend them tooth and nail.

Understanding why we do this is the key to discovering truth and making wiser decisions.

In this piece I lay out the overview of his argument and illustrate through a business example.

His argument leans heavily on an evolutionary bug in our brains that critical thinking strategies can resolve

He suggests there’s a bug in the evolutionary code that makes up our brains. Apparently, we have a hard time distinguishing between when cause and effect is clear, such as checking for traffic before crossing a busy street, and when it’s not, as in the case of many business decisions.

We don’t like not knowing. We also love a story.

Just like with Homer did in this short clip, our minds create plausible stories to fill in the gaps in other people's stories to construct our own cause and effect relationships.

The trick is to have some critical thinking strategies to help us evaluate other people's stories and our own. To help us avoid telling stories that are convincing and wrong.

We need to think about how these stories are created, whether they’re right, or how they persist. A useful ‘tell' is when we find ourselves uncomfortable and unable to articulate our reasoning.

A real life example brings his argument to life in an uncomfortably familiar way

Imagine a meeting where we are discussing how a project should continue, not unlike any meeting you have this week to figure out what happened and what decisions your organization needs to make next.

You start the meeting by saying “The transformation project has again made little progress against its KPIs this month. Here’s what we’re going to do in response.”

But one person in the meeting, John, another project manager, asks you to explain the situation.

You volunteer what you know.

“After again failing to deliver on their KPIs, we recommend replacing the project leader with someone from outside the organisation who has a proven track record with transformation programs. The delays are no longer sustainable.”

And you quickly launch into the best way to find a replacement team leader.

Mary, however, tells herself a different story, because just last week her friend, the project leader, described the difficulty her team was having with two influential leaders who were actively against the transformation program.

The story she tells herself is that the project leader probably needs extra support from the CEO and potentially also the Board.

So, she asks you, “What makes you think a new project leader would be more successful?”

The answer is obvious to you.

You feel your heart rate start to rise.

Frustration sets in.

You tell yourself that Mary is an idiot. This is so obvious. The project is falling further behind. Again. The leader is not getting traction. And we need to put in place something to get the transformation moving now. You think to yourself that she’s slowing the group down and we need to act now.

What else is happening?

It’s likely you looked at the evidence again and couldn’t really explain how you drew your conclusion.

Rather than have an honest conversation about the story you told yourself and the story Mary is telling herself, the meeting gets tense and goes nowhere.

Neither of you has a complete picture or a logically constructed case. You are both running on intuition.

The next time you catch someone asking you about your story and you can’t explain it in a falsifiable way, pause, hit reset and test the rigour of your story.

What you really care about is finding the truth, even if that means the story you told yourself is wrong.

Why am I sharing this story with you?

In Clarity First we teach people 10 specific questions to ask when evaluating our communication that helps us to see whether our ideas ‘stack up'.

These are incredibly powerful and help you ‘step back' from your own ideas to evaluate them critically.

Take a look at the Clarity First Program to learn more.

We help you communicate so your complex ideas get the traction they deserve.

Keywords: #critical thinking #decision making #kahneman

The Minto Pyramid Principle is a widely lauded approach for preparing clearer business reports.

Developed by a McKinsey & Company team led by Barbara Minto in the 1960s, ‘pyramid’ helps people use logic and structure to organise their ideas into a logical and coherent reader-focused argument.

At Clarity First we love this approach.

It enables us to think top down, draw out insights quickly and communicate complex ideas clearly.

However, despite much evidence from our own work and its popularity across consulting and business strategy teams in particular, very little formal research has been undertaken into its actual effectiveness.

Perhaps it was enough to say “It’s McKinsey: It’s good”.

However, Dr Louise Cornelis (another ex-McKinsey communication specialist) recently changed this when working with a series of Masters’ students at Groningen University in Holland.

She undertook a qualitative study to understand whether preparing a business report using a ‘top-down, reader-focused pyramid structure’ was actually helpful to the reader.

Dr Cornelis’ findings demonstrate some irony.

Writers and readers don’t always agree on what is ‘reader-focused’ unless the writer first educates the reader about what ‘reader-focused’ actually means.

Here is why that seems to be true.

#1 – Audiences are hard wired into their old habits

It seems that our readers are hard-wired into what they expect and can be confused by a new way of doing things unless it is explained to them.

In the case of business reports, many people are accustomed to receiving reports written with titles such as ‘Executive Summary’, ‘Background’, ‘Issues’ and a ‘Conclusion’ at the end and are quite lost when these are absent.

They can be confused by Pyramid reports that ignore these section titles, preferring to instead have customized titles that reflect the content of the report: a bit like newspaper headlines.

#2 – Consultants and others using the approach often forget to explain how their approach works

When, however, the approach is explained they not only like the Pyramid Principle approach much better, but can read the documents significantly more quickly.

Readers who were provided with a short description of the structure before reading the documents were able to grasp the main message from a document almost five times faster than those with no preparatory explanation.

Dr Cornelis found that people very much appreciated the Pyramid Principle report-writing approach but only when they understood what it was trying to do.

So the next time have a good idea: remember to ensure your significant others understand the benefit, even when the idea is specifically for the them.

Keywords: design your strategy, develop your storyline, research

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Louise Cornelis is a communication consultant based in Rotterdam. Louise specialises in helping her clients use structure and logic to communicate clearly, having learned her craft at McKinsey & Company and honed it by working with a wide range of clients since.

She particularly enjoys grappling with complex challenges that relate to helping others not only communicate clearly, but want to do so. The Clarity First team very much enjoys thinking about these challenges in collaboration with Louise.